Why Johnny Can't Math

The Decline of Math Education in New Jersey

Why Johnny Can't Read—And What You Can Do About It, published in 1955, exposed flaws in American reading education, particularly the shift from phonics to the "look-say" method. Today, Johnny faces a new crisis, not in reading, but in math with a change in math pedagogy that isn’t working for students. In New Jersey, 55% of fourth graders can't perform math at grade level, and by sixth grade, this figure jumps to 64%, according to Wakeup Call NJ. To make matters worse, New Jersey is one of eight states where students remain lagging in math due to damaging pandemic restrictions that lingered for 2 years.

Overall, New Jersey now nationally ranks 12th in Education, we can no longer claim that higher property taxes results in top tier education.

Find your school’s performance HERE.

Reform Math=Fuzzy Math

We could blame the pandemic, but New Jersey's math proficiency rates have been steadily declining for over a decade. The pandemic only brought to light the flaws in “fuzzy” math education that has been raging for almost three decades. New Jersey began pushing reform math in schools in 1996, when the State Board of Education adopted its first set of mathematics standards developed by Rutgers’s University’s New Jersey Mathematics Coalition. These standards emphasized a shift toward "standards-based education," which aligns with reform math principles such as “discovery learning” and “conceptual understanding”. The push for reform intensified with revisions in 2002 and later with the adoption of Common Core standards in 2010, further embedding reform-oriented approaches into the state's curriculum.

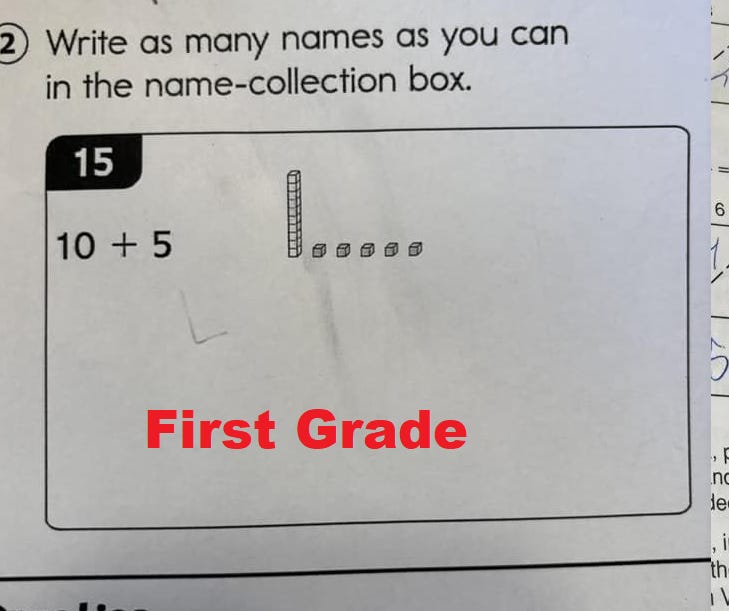

Reform math homework assignment examples below.

If you're frustrated with some of the fuzzy math homework that comes home, you're not alone. Unfortunately, this unusual approach hasn't been proven to accelerate math skills, the decline in math scores makes that evident.

An article written by educators Barry Garelick and Robert Craigen, highlights critical flaws in contemporary math education brought on by reformers that negatively impact students. According to Garelick and Craigen, the shift towards reform math has led to prioritizing inefficient procedures, discovery learning, and group work over mastering foundational skills like standard algorithms and repetitive drills. They argue that this approach often confuses students, delays their progress, and deprives them of the structured learning needed to build expertise. Critics contend that reform math sacrifices mastery for ideology, leaving many students struggling, parents frustrated, and without structured learning.

Cultural Bias Limits Math Goals

There isn’t one single reason for poor test scores, some of the problem IS cultural. In many Western cultures, it is socially acceptable, even normalized, to admit difficulty or disinterest in mathematics. People often say "I'm not a math person" without fear of judgment, and this sentiment is sometimes expressed with pride or humor. You never hear someone proudly declare, "I'm not a reading person," unless they're trying to explain why they still haven't finished that book club novel from three years ago. In contrast, admitting illiteracy or difficulty with reading is stigmatized and rarely accepted as a casual statement. This disparity reflects how our culture values literacy as essential, while treating mathematical proficiency as optional.

Many people think that mathematical ability is innate. THAT IS FALSE. This idea undermines the importance of foundational skills and effort. Cognitive science shows that success in both math and reading depends on building prior knowledge and practicing foundational skills. However, the misconception persists more strongly for math, leading many to give up prematurely.

Similarly, the idea that “boys better than girls at math” is stereotype definitely has deep roots in American culture, but its not universal. In East Asian countries like China, Japan, and South Korea, success in math is often seen as the result of effort rather than innate ability, and girls frequently perform as well as or better than boys. Similarly, in Nordic countries such as Finland and Sweden, known for their strong gender equality, math performance between boys and girls tends to be very similar, and the stereotype is much weaker. In regions like the Middle East and North Africa, traditional gender roles may still exist, but girls often outperform boys in school-based math assessments. Globally, research shows that cultural beliefs, confidence levels, and teaching practices influence the gender gap in math more than any biological differences, proving that the idea of boys being better at math is more cultural myth than fact.

This all goes back to the same premise, if you believe that you will do poorly in math, you will fulfill that prophecy.

Math is like any other skill, such as playing an instrument, learning tennis, or mastering chess. It requires practice, repetition, and a focus on mastery. Just as musicians perfect their craft through scales and athletes refine their techniques through drills, math demands consistent effort to build foundational skills. Without this emphasis on mastery, students struggle to develop the fluency and confidence needed to tackle more complex problems.

On a Personal Note

When my child first entered the public school system 15 years ago, I was deeply disappointed by the poorly scaffolded math program she was receiving. My daughter started first grade with the ability to add and subtract, but by January, she had lost all of her summer skills and could no longer do so. There were no math worksheets, no drills, and no emphasis on mastery. When I asked the teacher about the lack of drills, she laughed and said, "Oh, we don’t do that anymore."

My daughter was getting worse at math, and I couldn’t allow that to happen. The mathematician’s daughter struggling with grade school math was out of the equation. Frustrated, I vented to a colleague from China while at work. He shook his head knowingly and said, “The American education system is a mess, you need Kumon.” At that point I found most parents in STEM fields in New Jersey relied on tutors and learning centers to get their children through elementary school so that they would have the skills for High School Algebra I.

By 2012, my frustration had grown, and I joined other STEM professionals to advocate for change. Around that time, I also authored an article titled, Statistician’s View of Constructivist Math, where I outlined my concerns about the shortcomings of constructivist/reform approaches in mathematics education.

Eventually, I switched my daughter to a private Catholic school that offered a traditional math program. Fast-forward to today, and I am proud to say that she is now enrolled in an engineering program at a college ranked number five for undergraduate aerospace engineering (U.S. News & World Report’s, 2024-2025 rankings).

Guinea Pigs in Math Experiment

I see reform pedagogy as a failed experiment on students, implemented without sufficient evidence of its effectiveness. By shifting away from traditional methods like drills and mastery-based learning, classrooms became testing grounds for unproven educational theories. This approach raised concerns about declining foundational skills, particularly in mathematics, as students are subjected to a large-scale trial of new teaching methods.

So why fix math education it if it’s not broke?

Eventually I realized that the relentless push for experimental pedagogy in our schools isn't about improving education, it's about lining the pockets of publishers like Pearson. With each new pedagogical fad, a fresh wave of textbooks, manipulatives and resources becomes "essential," rendering the old ones obsolete. This constant churn creates a lucrative cycle where schools are pressured to adopt the latest methods, regardless of a proven track record. The real losers in this scheme are the students, who become guinea pigs in untested educational experiments, and the taxpayers, who foot the bill for these expensive, often ineffective, resources. Meanwhile, educational publishers laugh all the way to the bank, fueled by the endless appetite for "innovation" in our schools.

50 years in public education. I have probably heard “I suck at math” thousands of times from students and parents. In fact, as I was typing this, “I suck at ….” Math was the first word AI generated. I think we’ve become so accepting of not understanding math as almost a given, in many cases I think we’ve stopped trying.

I went to public school in Brooklyn, NY, starting in the early 1960s. Nobody ever accused me of being the sharpest tool in the shed, but I exceeded grade-level reading, comprehension, and math until the rascal came out of me in Junior High School. What I didn't learn was because of me, not the school. Today, it is 110% the school's fault. BTW I ended up doing ok and am enjoying retirement.